Book Review – Celebrating 20th Century shops.

© Batsford

Consumers’ shopping experiences are focused wholly around the design of the internal physical space that creates the intended ambience and environment to perfectly showcase a retailers’ product ranges. Meanwhile the external bricks and mortar structure of these shops is largely overlooked and customers are pretty much oblivious of their architectural merits.

Looking to address this situation is the forthcoming book: ‘100 20th Century Shops’ (published by Batsford on November 9). It has been written by the Twentieth Century Society – that seeks to protect buildings with outstanding architecture dating from 1914 onwards – as it recognises that many buildings on UK high streets are under threat from developers.

If shoppers haven’t been bothered about them up to now then why should they take notice now, you might ask. The authors point out that as the role of the shop is changing and the retail landscape is having to adapt to a multi-channel world then there should at least be a discussion about how the country’s existing buildings can be potentially repurposed rather than just being bulldozed. The risk is that the country would not only lose bricks and mortar but also the histories of these structures would be gone forever.

The Society has selected 100 buildings that have been constructed within the last century and which were either built as shops and remain so, were once shops but have since been repurposed, or have become shops and currently trade as such. The connection between them all is that they have features that mark them out from typical retail structures.

The book is split into six time-frames within which are selected distinctive buildings from that period. Each is given a profile alongside a current photograph and in some cases there are also archive images to show the stores in their heyday. These profiles are easily digestible and although the focus is on the design features of the buildings there is sufficient other detail to satisfy readers with an interest in the retail world.

What is most illuminating is the incredible variety of buildings featured. They run the gamut from extremely grand and distinctive stores such as Heal’s, Vigo House (that now houses Burberry) on Regent’s Street and Boots in Bexhill-on-Sea with its moderne style right down to small independent shops like Kennedy’s Sausages in South London, Birds Bakery in Nottingham, and Oakwood Fish Bar in Leeds.

The style of the book is particularly suited to dipping into and randomly selecting a page. This strategy will no doubt reveal some new gems to readers and also provide much greater knowledge about stores that they might have felt they were well versed. Some of my highlights included a number of former Burton’s menswear stores from the 1930s onwards that often had billiard halls on the first floors, which highlights that mixing retail and leisure is hardly a new phenomenon.

The Derry & Toms department store on Kensington High Street is a good example of how stores can run through multiple lives as it has since become Barkers, then Biba and today the ground floor houses various well known retailers. Probably the best example of the changing role of stores is the lovely Art Deco designed Havens shop in Westcliff-on-Sea that was initially a family owned department store in 1901 but has since been through various iterations before alighting on its current role as a hybrid store, community centre, café, rehearsal rooms, and market stalls space.

The latter sections of the book – 1970-1979 and 1980-onwards – very much highlight the rise of the shopping centre as a key feature of the retail landscape. This is both in town centres and out-of-town. The 1970s certainly heralded an era of very distinctive structures, with concrete very much coming to the fore. To many people these structures can feel rather brutal in design and notable inclusions are Blackburn Shopping Centre, Queensgate Market in Huddersfield and the Irvine Centre in Scotland. Whether you like them or not there is no doubting their distinctiveness and how they came to define a certain period in retail development.

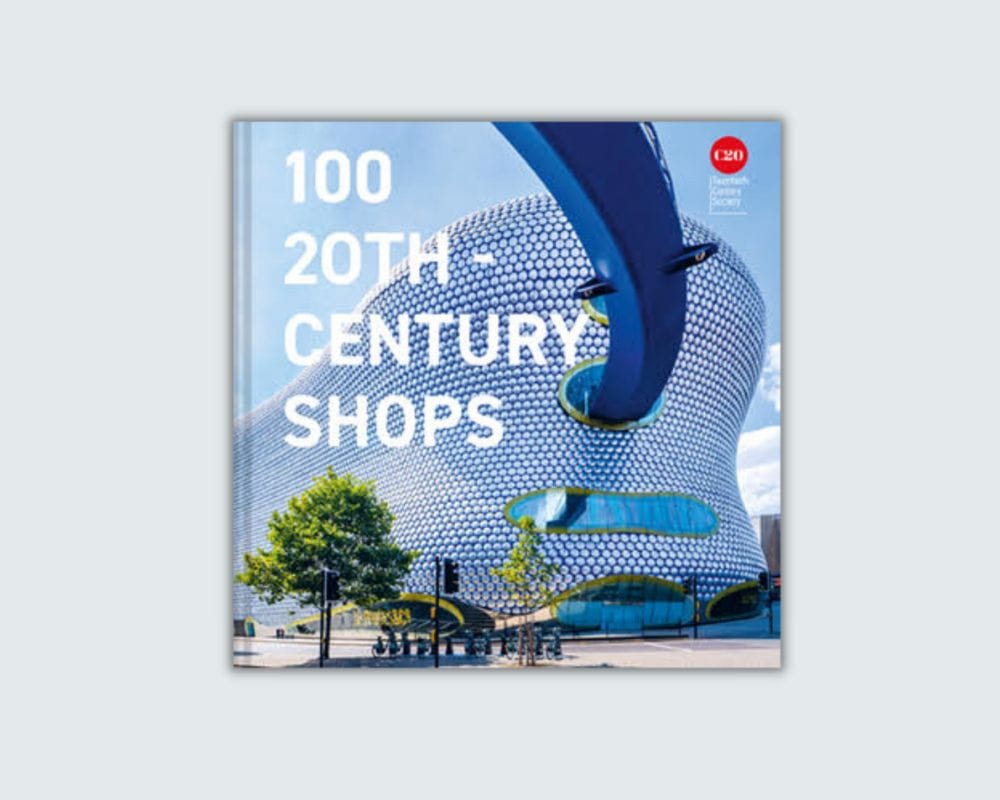

More recent notable creations include the incredibly dramatic Selfridges in Birmingham with its exterior coating of 15,000 anodised aluminium discs that makes it one of the most distinctive stores in the UK. Its fluid, wavy exterior is replicated inside with a wave-form shape to the floors. The final entry in the book is equally impressive – Coal Drops Yard in London’s King’s Cross, which is a repurposing of the industrial buildings that serviced the rail station and now houses high-end independent stores alongside various restaurants and bars.

Along with the 100 store profiles the book also includes a number of chapters focusing on key aspects of the retail sector across the past century written by experts in their fields. These contribute to forming a much more broadly appealing publication.

These chapters are both enlightening and very readable in style. ‘Markets, Arcades, Precincts and Shopping Centres’ highlights how the advent of cars brought in shopping precincts for pedestrian safety and that the first mall with department stores as anchors appeared in the US in 1951 and was widely copied in the UK thereafter. The first fully enclosed mall appeared in Elephant & Castle in South London in 1962 at a time when the shopping centre became a leisure destination rather than a place to purchase life’s essentials. The fact that 488 shopping centres were built between 1965 and 1983 highlights the appeal of the format over a number of decades.

The chapter titled ‘The Co-operative Movement and its Stores’ paints a picture of an incredibly popular way to shop as the Co-op attracted an impressive six million members by the late-1930s when one in 30 stores was a Co-op outlet. Needless to say this encompassed an array of store types, many with strong architectural features and a number of them are profiled in this book. The number of Co-op stores in England hit a peak of 28,000 by the early-1960s but by 1985 this had collapsed to only 3,000, which is reflected in the fact a number of these buildings now house other retailers.

It is no great surprise that the publication also includes a chapter on ‘Department Stores’ as they have seen their fortunes rise and fall dramatically within the time-frame of the book. The first example of this new way of shopping was Bon Marché in Brixton in 1876 and the ground-breaking Selfridge’s was to follow in 1907 with its steel-frame construction. A dramatic expansion of department stores then ensued with numbers doubling to 500 between 1914 and 1950, as various innovations were introduced such as elevators that increased their appeal to shoppers.

Such stores continued to open, fuelled in the late-1990s by the planning system in the UK swinging towards town centre redevelopment rather than out-of-town malls, but this was to cause major problems when the internet sucked sales from physical stores and department stores chains have suffered particularly severely ever since.

[Highlighting how London has been affected is another publication: ‘London’s Lost Department Stores’ (published by Safe Haven). It is worth a read for its detailing of the incredible ups and sadly the ultimate downs of these grand stores in the UK’s capital city].

The final flourish in this appealing book is the chapter on ‘The Twentieth Century Boutique’ that tells the story of what was a London-based phenomenon in the UK having followed the trend from Paris. It involved pre-existing buildings being dressed and staged by professionals and was originally focused on independent fashion stores but then spread to other goods like perfume, hats and accessories. ‘Swinging London’ in the 1960s was the high point of boutiques in the UK as Chelsea, Carnaby Street and Mayfair became home to many such stores – including the renowned Mary Quant’s Bazaar in 1955.

The 1970s saw Vivienne Westwood’s store on the King’s Road change its format frequently – Let it Rock, Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die, and then Sex. This repurposing and constant change invariably excited shoppers and sounds just the tonic for today’s reinvention of the physical shopping environment. It further highlights the point that nothing is completely new.

Certainly the Twentieth Century Society would argue that what we don’t need are new buildings when we already have many architectural gems littered across our high streets that just need a dose of repurposing or a redressing. This book puts forward some strong evidence towards this cause.